Between Code and Clausewitz

War is more technical than ever. A Marine intelligence officer reflects on coding, Clausewitz, and why tomorrow’s leaders must speak both.

On thinking like a programmer and operating like a strategist

Learning the Language of Logic

“Sir, AI doesn’t work that way.”

That’s what I almost said to the commander—before I realized he wasn’t wrong. He just needed a translator.

I didn’t start off trying to become a strategist. Or a coder, for that matter.

Truthfully, I’ve never been naturally inclined toward math or STEM. I admired the elegance of it—the clean lines, the structured thinking—but I struggled more than I let on. I studied computer science mainly because my mom believed it would open doors. And because I had two phenomenal teachers at Stuyvesant—Mr. Mykolyk and Mr. Dyrland-Weaver (“DW”)—who made the subject feel alive.

Thanks to them, I stuck with it. The school I attended—Stuyvesant High School in New York City—had one of the most rigorous public computer science programs in the country. I started with Intro to CS as a sophomore, where I learned foundational concepts like recursion and logical structures. I moved on to AP Computer Science in my junior year, working with Java and JavaScript, and even building websites from scratch using HTML and CSS. I capped it off with a Software Development course in my senior year, where we were pushed through real-world development cycles. Some classmates went on to commercialize their projects. I built a matchmaking app for fans of anime and Star Wars. It was niche, and it didn’t go anywhere—but it taught me how design choices shape user behavior.

I learned to break problems into logical parts, debug systems line by line, and think in loops and abstractions. I even mentored underclassmen at the after-school CS Dojo, helping them wrap their heads around state machines and basic computational theory.

I was never a prodigy. But I became fluent enough to be slightly dangerous. I could trace logic. I could sense structure. I liked the clarity of it all—the sense that, in code at least, there was always a right answer.

But even then, something else was tugging at me.

The Human Pull

While I was learning to code, I was also devouring books on war, diplomacy, and history. I stayed up late playing grand strategy games where alliances crumbled, borders shifted, and empires collapsed from a single miscalculation. I wasn’t just fascinated by how systems worked—but by why they were built in the first place. Why they broke. Why people made the choices they did.

That’s when I discovered Clausewitz—entirely by accident.

I was in high school, preparing for a Model United Nations crisis committee on global security. During my research, I stumbled upon a name that kept surfacing in military theory circles: Carl von Clausewitz, a 19th-century Prussian general and philosopher of war. Curious, I pulled up excerpts from On War. It wasn’t easy reading—but it stopped me in my tracks.

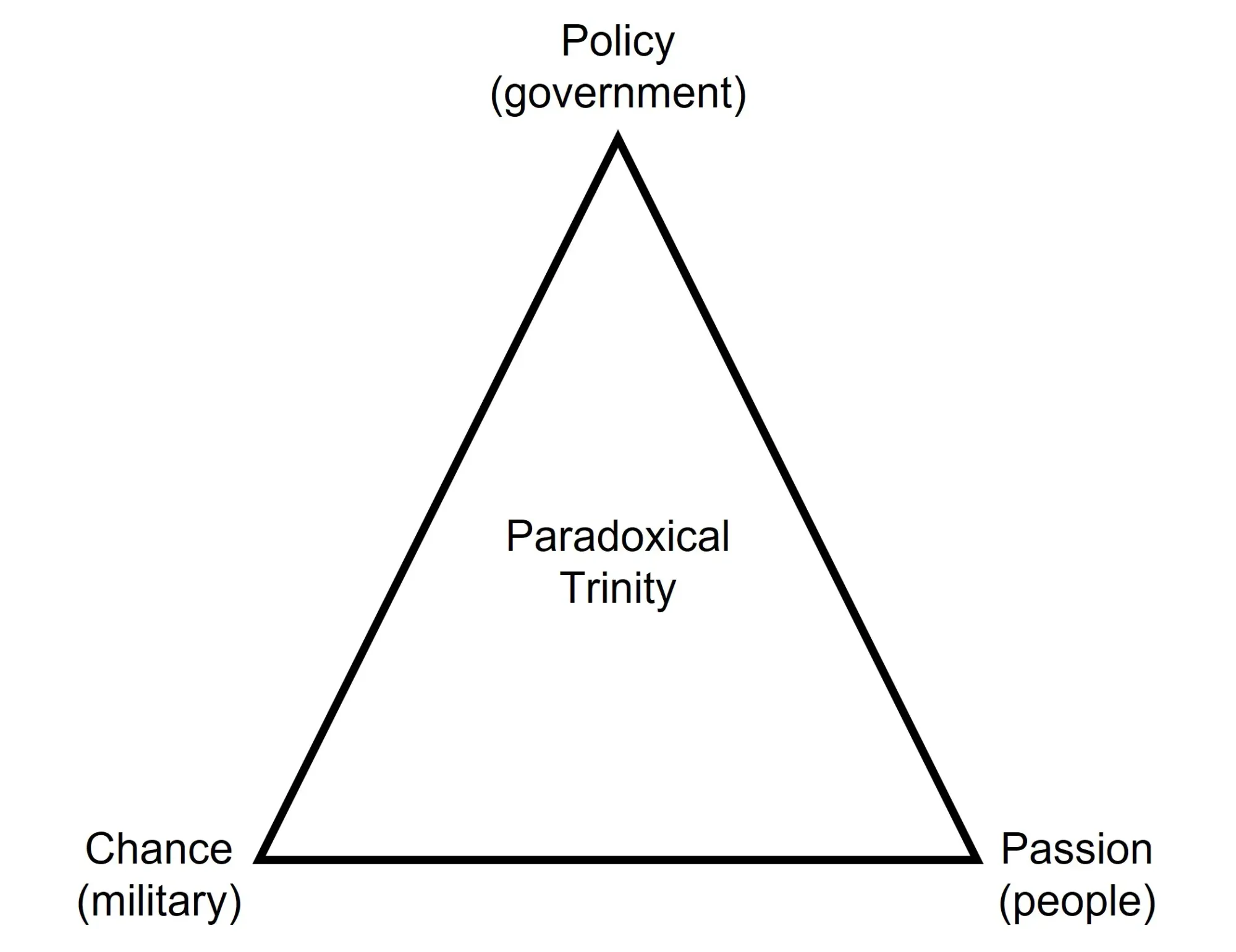

Clausewitz argued that war isn’t just about weapons or plans—it’s about people. About emotion, uncertainty, and political purpose. He described war as a “paradoxical trinity”: a constant interplay between violence and passion (what he called primordial hatred), chance and uncertainty (the fog and friction of the battlefield), and reason and policy (the rational aims of the state). He wrote that war is the continuation of politics by other means—a quote I’d see again and again, but only later truly understand.

I’d never seen war framed that way before. Not as a machine to optimize—but as a deeply human phenomenon. Messy. Contradictory. Strategic. Moral.

And somehow, it made perfect sense.

Even as I was learning how machines processed the world through logical gates and input-output loops, I was beginning to grasp how humans processed conflict—through fear, bias, partial knowledge, and intuition. Clausewitz gave me a vocabulary for things I’d only sensed: that in any complex system, the hard part isn’t building it—it’s understanding how people behave inside it.

So even as I stayed immersed in coding—debugging programs, thinking in abstractions—I was also drawn to something fuzzier, more interpretive. I joined my school’s debate team and dove deep into Model UN, learning to argue policy, anticipate moves, and think like a diplomat or general under stress. I engaged deeply in AP U.S. History with Mr. Sandler, and AP English with Mr. Garfinkel and Ms. Fletcher—classes where framing and narrative mattered just as much as facts.

Eventually, I pivoted.

In college, I studied international affairs and Japanese literature—a combination that raised eyebrows, but made perfect sense to me. One gave me tools to understand geopolitics, state behavior, and power. The other gave me access to a culture whose values—restraint, discipline, beauty beneath form—had long fascinated me. I wasn’t interested in surface-level cultural appreciation. I wanted to go deep. To understand how nations, like people, remember war. How they make meaning out of ruin. How the past shapes the patterns of the present.

I spent a year living in Tokyo, studying at Waseda University. There, I took a few courses taught entirely in Japanese and trained at a higher level on the ballroom dance team. I commuted through Shinjuku Station, read policy papers in cafes, and lost myself in side streets filled with contradictions: ancient shrines tucked beside glowing billboards, trains that ran to the second while people carried generations of emotional weight beneath the surface. It was a year of immense personal transformation—a confrontation with loneliness, beauty, and clarity all at once.

At night, I’d practice dance until my legs were sore, then return to my apartment and write. I wasn’t always sure what I was chasing—but I knew it mattered. I took long walks through unfamiliar neighborhoods just to see how different lives moved. I studied Japan’s pacifist constitution, its security relationship with the United States, and its memory politics surrounding World War II. I noticed how silence could be a form of expression. How cultural posture—like military posture—communicated more than words.

Back in D.C., I wrote a senior thesis on postwar reconciliation between Japan and the Philippines. It was more than an academic exercise—it was personal. I was born in the Philippines, a former colony brutalized by Japanese occupation. And yet here I was, an American citizen who loved Japan, writing in its language, studying its literature, dancing to its music. That tension was never lost on me. I didn’t try to resolve it—I tried to understand it. The work became an exploration of forgiveness, narrative, and national identity. Of how countries reckon with what they’ve done—and what they’ve become.

Outside the classroom, I competed in ballroom dance competitions. Waltz, foxtrot, tango—each one a study in precision and presence. Dance became my way of living out the things I studied: timing, leadership, rhythm, adaptation. You lead not with force, but with clarity. You learn to feel your partner’s axis, to sense intention before motion. That sensitivity—the attunement to tempo, alignment, subtle shifts—is something I carried with me into strategy and service.

Even then, I wasn’t done with code. The syntax faded, but the thinking stayed.

I still sketched logic flows in the margins of my policy notes. I approached diplomacy cases the way I once approached debugging: isolate the variable, trace the input, test assumptions line by line. When I wrote my thesis, I built conceptual diagrams that looked suspiciously like architecture charts—actors, interactions, feedback loops, bottlenecks of trust. I realized that the way I analyzed a coalition breakdown in a Model UN scenario wasn’t so different from tracing a function failure in a program. It was all systems thinking—just with messier inputs.

Even dance, at that point, started to feel like code in motion. Ballroom has rules, structure, protocol. There’s a visual syntax to a proper lead. A conditional rhythm to how a follow reacts. If tension shifts, then step here. If no resistance, continue momentum. It was embodied logic—an elegant feedback loop in real time. It trained me to be precise without rigidity. To read signals that weren’t verbal or digital, but physical and emotional.

In everything I did, I was unconsciously thinking like a coder—but one working in analog.

And more than anything, it taught me how to think when things broke. Code doesn’t care how smart you are. It just runs or it doesn’t. If something fails, it’s because something doesn’t make sense—yet. You learn humility. You learn to sit with the problem and ask better questions. That mindset carried with me long after I stopped compiling programs.

Later, when I found myself in a SCIF staring at targeting data, or in a planning cell trying to architect a kill chain, I realized I was doing the same thing: pattern recognition, debugging, system-level reasoning. Only now, the stakes weren’t grades or dance scores. They were real-world outcomes. Lives. Escalation thresholds. Misreads that could spiral into something bigger.

So no—I never really left code. I just started applying it to people.

To policy.

To conflict.

To war.

The Operator Between Worlds

Today, I’m a Marine Corps intelligence officer.

My job is to anticipate conflict before it erupts. To map adversary systems, track behavioral patterns, and help enable strikes that are not only precise, but purposeful. I operate in the space between what’s observed and what it implies—between analysis and action. Between dots on a screen and decisions in the field.

That’s where I belong: between Clausewitz and the compiler.

My computer science background helps me understand the technical spine of the modern battlefield—ISR tasking flows, digital kill chains, comms architectures, latency bottlenecks, and the fragility of networks under pressure. I don’t build software anymore, but I still think like someone who does. I trace inputs to outputs. I question assumptions about stability. I understand that even the cleanest interface is hiding complexity underneath.

This matters because today’s fight is increasingly shaped by systems—and most commanders aren’t system-builders. They’re warfighters. Infantry officers. Aviators. Operational leaders forged through reps and sets in the field, not in source code. Their experience lies in maneuver, leadership, risk calculus—not in how a multi-domain data pipe gets choked by a satellite hop or what a sensor fusion node needs to process effectively. That’s not a deficiency. That’s why they have staff.

My job is to be the bridge. To interface upward with command intent and downward with technical implementation. To make sure the engineers aren’t optimizing for irrelevant problems—and that the commander’s vision is actually executable within the constraints of the architecture.

But here's the truth: I wouldn’t be effective in that role if I only had the technical lens.

What makes the difference isn’t just what I know about data—it’s what I understand about people and tactics.

Because I’m a warfighter, too. And what allows me to translate between systems and strategy is not just code fluency—it’s human fluency.

My liberal arts training gave me the framework to think in context. To hold competing narratives. To move between quantitative models and qualitative meaning. Clausewitz taught me that war is not just violence—it’s the pursuit of political will through force. Literature taught me how stories shape perception. History taught me to pattern-match across eras. Philosophy taught me to interrogate values. And debate trained me to speak clearly under pressure—across disciplines, across cultures, across rank structures.

That’s what allows me to brief effectively. Not just with technical accuracy, but with narrative force.

I can tell you what the enemy is doing, and what it means. What it signals, what it conceals, and where it fits in the broader schema of intent. I can sense when a behavior is posturing versus preparation. When a pattern breaks. When a data point has a political shadow.

This isn’t about being smarter. It’s about being whole. About knowing that no strike recommendation, no intelligence product, no collection strategy exists in a vacuum. Every action we take is embedded in a web of perceptions, interests, histories, and constraints. And when you recognize that, you don’t just inform decisions—you elevate them.

That’s why I say I live between domains—not just because I translate between engineers and commanders, but because I fight from that space. Strategically. Morally. Humanly.

Between the cold clarity of logic and the messy heat of war.

Between systems and stories.

Between the digital and the decisional.

The operator between worlds.

Bridging the Gap

Not long ago, a commander pulled me aside with a question that wasn’t easy to answer:

“How might adversary AI and machine learning be used to find and fix us in a fight?”

He wasn’t asking out of idle curiosity. This was part of real-world planning. There were exercises on the horizon, postures being shaped, kill chains being built. His question was simple—but its implications were complex, and the answers wouldn’t be found in a PowerPoint slide or a doctrine pub. What he needed wasn’t a lecture on algorithms. He needed insight that could inform action.

I’m not a machine learning engineer. I don’t write models. But I understand the architecture well enough to know how the pieces fit: how AI systems ingest data, how they might be trained to recognize radar signatures, force patterns, or emitter behaviors, and how they could be operationalized to shorten sensor-to-shooter timelines. I also knew how the commander thought—his mental models, his language, his appetite for risk. And so, I translated.

I framed the issue in terms that made operational sense:

Here’s what it would take for them to do that.

Here’s what they’d need to see.

Here’s how they might target our signatures—or mistake a decoy for the real thing.

Here’s what that means for how we posture and move.

Here’s how we counter it—not just tactically, but cognitively.

I didn’t just give him a technical answer. I gave him a decision space.

Because in that moment, the most valuable thing I brought wasn’t deep expertise—it was connection. Between domains. Between mindsets. Between what the engineers might design and what the commander needed to understand. Between architecture and action. Between sensing and striking. I helped him see how it all fit—not as a system diagram, but as a battlespace.

That moment changed how we postured for the mission. Not because I was the smartest person in the room—but because I could bridge the room. Because I could carry the question across disciplines, and return with something meaningful.

I’ve built target packages—collections strategies, prioritized sensors, strike recommendations. But I’ve also built context—framing decisions, identifying assumptions, drawing the thread between what we know and what we think we know.

And sometimes, I think that’s the real skill:

Not knowing everything, but knowing how to hold both.

The detail and the judgment.

The structure and the story.

The signal and the human who reads it.

That’s what it means to bridge the gap—not just in the military, but anywhere complexity meets consequence. Where we need more than answers. We need translation, synthesis, and the clarity to act.

Why It Matters

A lot of junior officers either dive headfirst into tech or avoid it entirely. Many treat Clausewitz and code as opposites. I don’t. I see them as tools—each incomplete without the other.

Clausewitz taught me that war is the continuation of politics by other means. Computer science taught me that elegant systems fail when misunderstood. Together, they help me operate in a world that is both digitized and deeply human.

And make no mistake—the battlefield is more technical than ever. Targeting today isn’t just about maps and munitions. It’s about ISR platforms feeding into sensor networks. AI models prioritizing kill chains. Fires requests riding on data links. Cyber and electromagnetic effects overlapping with kinetic ones. The line between what’s digital and what’s physical is gone. In many ways, it was never there to begin with.

But this isn’t just about war. The same convergence is happening in every field. Business, governance, healthcare, logistics—any industry where humans must make high-stakes decisions with partial information in complex systems. If you don’t understand how information moves, how algorithms prioritize, or how infrastructure constrains options, then your vision is distorted. You’re not operating—you’re guessing.

And yet, we don’t need everyone to become a software engineer or systems architect. What we need—whether in a command center or a boardroom—are translators. People who can move between worlds. Leaders who are technically literate enough to ask the right questions and morally grounded enough to know which ones matter. Thinkers who don’t just understand tools, but how tools shape behavior. People who recognize that no model is neutral, and no data set speaks for itself.

I’m not an engineer. I’m not a data scientist. But I know enough to be dangerous—and more importantly, I know enough not to treat systems like magic. Even the most advanced algorithm still needs a human behind it—someone with judgment, context, and a sense of what’s at stake.

We have to stop thinking of “technical” and “human” as separate domains. The best analysts I’ve worked with could code and brief. The best commanders could understand an API just well enough to know when to push for better integration. And some of the best conversations I’ve had weren’t with military experts—but with civilians who knew how to frame a problem clearly, challenge assumptions, and tell a better story with the data.

Because that’s what we need more of: people who can move fluidly between systems and people. Who can hold both logic and friction in their heads at the same time.

This isn’t just a military imperative. It’s a civic one. As our institutions get more complex, we need more people who can see both the machine and the meaning. Who can operate between policy and platform. Between backend and impact. Between code and Clausewitz.

We need more military professionals—especially junior officers—who can think this way. Not to write code, but to understand it. Not to become engineers, but to lead alongside them. To think technically. Brief humanly. Decide morally.

To live and operate between both worlds.

Between precision and uncertainty. Between data and doubt.

Between kill chains and cadence.

Between code and Clausewitz—where warfighters, and leaders of all kinds, learn to think in both patterns and people.

The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.