Okinawa: One Island, Two Maps

I. Two Lenses, One Island

My apartment sits at a point of intersection—across the street from a major U.S. military base, across a narrow road from Araha Beach, and fifteen minutes’ walk from the neon sprawl of American Village. Chatan, the town I live in, hugs the western shoreline of Okinawa’s main island, roughly halfway between the island’s capital, Naha, and its northern training ranges. The beaches here face the East China Sea, so by late afternoon the horizon becomes a stage for sunsets that shift from deep orange to pale lavender in the space of minutes. Behind the beachfront lies a dense grid of apartment blocks, family-run shops, and the concrete walls of U.S. installations. Their gates open directly onto the same streets where tourists browse souvenir stalls and teenagers skateboard past taco stands. The two worlds don’t touch so much as overlap, sharing the same narrow strip of pavement.

Five minutes from my door is Chirugawa Soba, a squat, whitewashed building with a hand-painted sign and a small parking lot perpetually occupied by small boxy Japanese cars. Inside, the air smells faintly of pork bone and bonito flakes. The tables are scuffed from decades of elbows, and the sound of sanshin—the traditional Okinawan three-string and precursor to mainland Japan's shamisen—is pervasive. The island’s signature dish arrives in a deep ceramic bowl: thick, chewy wheat noodles in a clear broth layered with pork and fish stock, topped with slices of tender soki rib that nearly slide off the bone. Okinawa soba is nothing like the buckwheat version served on mainland Japan—it’s heavier, simpler, and unapologetically generous. Food for laborers, divers, soldiers, and grandmothers. The owner doesn’t bother asking for my order anymore. She just points to an empty seat, sets down the familiar steaming bowl, and moves on to the next customer.

On days when I’m not driving to work, I cut west toward Araha Beach. It’s less than five minutes away, and the route passes a Family Mart convenience store whose fluorescent lights are always on, even in midday sun. Salarymen in short-sleeved shirts queue for fried chicken; schoolkids jostle for the ice cream freezer. From there, the walking trail runs along the water, past palm trees and basketball courts, linking Araha to American Village. American Village is a strange hybrid: part shopping mall, part seaside boardwalk, part neon-lit imitation of a U.S. beach town, complete with kitschy tourist trap stores and faux–Route 66 signage. Along the trail, I pass joggers, couples taking wedding photos on the sand, and parents picnicking while their children hunt for seashells.

Above it all, there’s almost always movement—F-35 stealth fighters banking toward Kadena Air Base to the north, Ospreys beating the air on their way to Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to the south, their blunt silhouettes cutting across the horizon. The locals complain about the noise, and I can’t blame them. The vibration hits your ribs before you even register the sound.

On a map, these places would look scattered—a base here, a beach there, a shopping district in between—but on foot they fold into a single continuous loop. One moment I’m stepping off the sand into the glow of American Village; the next I’m home, still tasting charcoal-grilled chicken from Kushikado yakitori, where the middle-aged proprietress—head wrapped in a towel—calls after me in machine-gun Japanese too fast for even my fluency to catch. That’s the Okinawa I walk every day, and the one that makes this place feel like home.

II. The Chessboard

Okinawa stretches like a comma in the East China Sea, the largest in a subtropical chain of islands arcing from Japan toward Taiwan and the Philippines. Strategists call this arc the First Island Chain—a line of landmasses that forms a natural barrier along the western Pacific. For decades, military planners in both Tokyo and Washington have studied it, sketched it, and gamed out how to defend or breach it. In war games, the islands become stepping stones; in reality, they are home to nearly two million people.

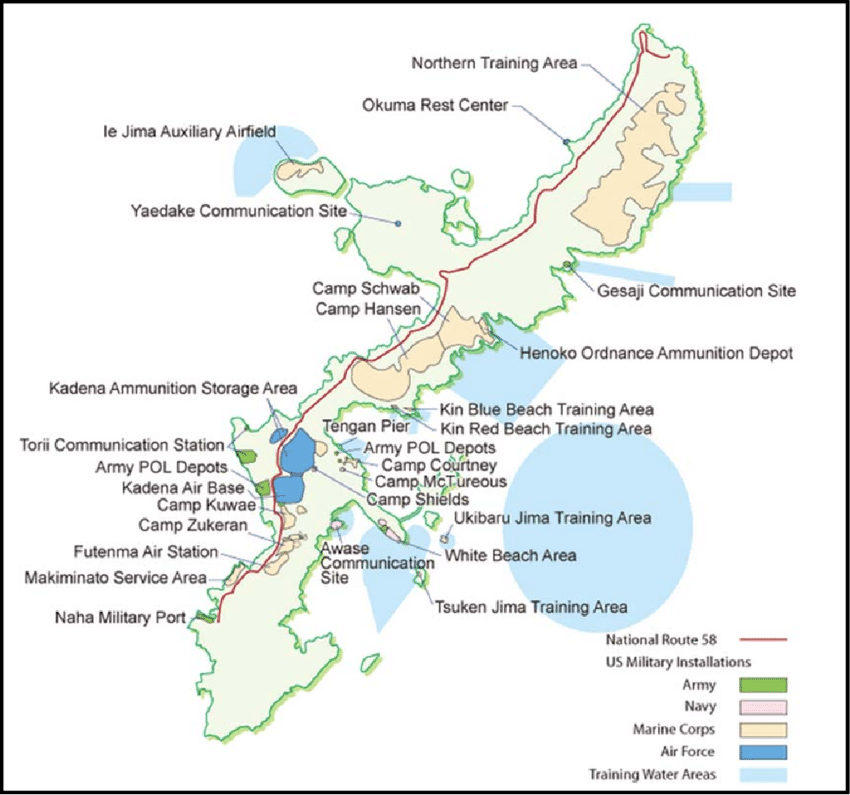

Okinawa’s location makes it both a forward outpost for the United States and a vital anchor for Japan’s own defense. That dual identity is etched into the island’s very layout. Kadena Air Base, the largest U.S. Air Force installation in the Pacific, dominates the central plain with its twin runways and sprawling maintenance hangars. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma sits further south, its single runway squeezed between neighborhoods and city streets, a reminder of how little flat ground the island offers. Other sites—logistics hubs, ammunition depots, communications nodes—dot the length of Okinawa, many hidden in forested hills or behind nondescript gates.

The concentration of U.S. military infrastructure here is no accident. After the Battle of Okinawa in 1945—the last and bloodiest major battle of the Pacific War—the United States occupied the island and retained control until 1972, long after the rest of Japan regained sovereignty. That legacy still shapes everything from land use to politics. For planners, the island is a launchpad for humanitarian aid in peacetime and a forward bastion in crisis. For many locals, it is also a reminder that the war’s footprint never entirely left.

To someone looking down from a reconnaissance satellite, the pattern is unmistakable: Okinawa is a platform. But a platform is not the same thing as a place. The same roads where I dodge schoolchildren on bicycles are MSRs—military supply routes—on someone’s operational overlay. For most Okinawans, these dual uses have been a fact of life for generations. For the United States, they are assets in a posture that spans the Pacific. For me, they’re the second map I carry in my head, layered under the one marked with soba shops, dance halls, and convenience store coffee machines.

III. The Friction Between Lenses

Not everyone here sees the two maps the same way. The Japanese government and the Self-Defense Forces view Okinawa as essential to the nation’s security. Washington sees it as an irreplaceable forward presence in the Pacific. But for some Okinawans, the U.S. military footprint is a burden they never chose. Protests still gather outside base gates, though the crowds have grown smaller than in the 1990s. Their signs are often handwritten in black paint: Henoko kichi hantai — “No to the Henoko base.” The chants are steady, almost metronomic, punctuated by the beat of hand drums.

I’ve passed by these demonstrations on my way to work a few times. Sometimes the protestors make eye contact, sometimes they don’t. Once, an older man in a baseball cap nodded at me as I drove through the gate, his expression unreadable—not hostile, not warm, just aware. Anthony Bourdain once sat down here with former governor Masahide Ota, who spoke plainly about the unfair weight the island has carried since the war. Standing outside the wire, watching a line of uniformed Marines head for the chow hall, it’s not hard to see his point.

That distrust isn’t only about noise or land use. Some of it comes from darker chapters—cases where U.S. service members committed crimes here, including sexual assaults that left deep scars in the community. Incidents like those are rare compared to the daily reality I see in my unit, but rarity doesn’t blunt their impact. On an island this small, every headline echoes for years. It’s a shadow the rest of us carry whether we deserve it or not, another weight added to the uniform alongside the mission.

When I’m in uniform, I’m part of that weight. Another Marine in woodland cammies, another American face behind the fence. Off-duty, though, I slip back into something closer to my college self: an Asian-American with a degree in Japanese Language and Literature, who still reads Natsume Sōseki and Osamu Dazai, and who spends Wednesday nights dancing bachata at Bailando on Gate 2 Street. There, the separation between local and military blurs. A Peruvian-Japanese instructor counts the rhythm of bachata in English, an Air Force airman spins a local university student, and everyone laughs when someone misses the beat. For a few hours, no one cares about what’s on either map.

Sakiko—my partner—doesn’t think about Okinawa as a strategic chessboard. To her, it’s home—warm people, good food, the coastline she’s known her whole life. She grew up with the sound of aircraft overhead, but it doesn’t shape her days the way it shapes mine. Her view reminds me that I’m a guest here, sometimes welcome, sometimes not. That awareness is constant, even when unspoken. It’s an internal counterweight to the part of me that briefs aircraft ranges and force posture.

The friction isn’t a contradiction so much as a coexistence. Two truths, both valid, living side by side: the Okinawa I walk and the Okinawa I brief. Learning to carry both without letting one erase the other is its own kind of discipline.

IV. One Island, Two Maps

Some evenings, I’ll walk the beach trail back from American Village with the last light bleeding into the sea. The air smells faintly of grilled meat from a yakitori stand, and the American Village's lights begin to flicker on behind me. Wedding photographers bark instructions in Japanese to a nervous couple posing barefoot in the surf. Overhead, an F-35 traces a slow, deliberate arc toward Kadena, its afterburners glowing briefly before the sound rolls in like distant thunder.

In that moment, the two maps are both true. On one, Araha Beach is a waypoint along a logistics corridor, a landmark beside an air route leading deeper into the Pacific. On the other, it’s where children dig moats in the sand and teenagers race each other to the pier. Neither cancels the other.

Living here has taught me that these two maps aren’t competing for space—they’re layered, transparent sheets laid over the same ground. The chessboard will always be there: the range rings, the supply routes, the airfields marked with alphanumeric codes. But so will the taste of pork broth at Chirugawa Soba, the towel-wrapped smile of the yakitori proprietress, and the gold shimmer of the East China Sea at sunset.

I’ve lived in places where the map and the ground matched exactly—cities like New York, where ambition and geography follow the same grid, or rural stretches of the Philippines, where the map is barely needed because everyone knows the way. Okinawa isn’t like that. Here, the map depends on who’s holding it, and what they expect to find.

For me, the island I walk every day and the island I brief are not the same—but together, they make the only Okinawa I will ever really know. And maybe that’s the point: maps are never the place, only the lenses we choose to see it through.

The opinions expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense, or any part of the U.S. government.